As a society, our current approach to mental health is damaging and limiting. There is a tendency within the media and support agencies to assume a continual rise in emotional difficulties among the young. We are told—in very general terms—that it is virtually impossible to escape mental health damage caused by factors such as engagement with social media, the fallout from Covid-19 lockdowns, and peer pressure. While some children and teenagers have negative experiences, this is not the case for all children and teenagers – yet we act as if it is. One problem with embracing this deficit model of mental health is that it leaves little space to show children and young people how to develop resilience in the face of life’s challenges.

Over a four-year period, I worked with teenagers to develop supportive and creative techniques which we used to work through difficulties and build emotional resilience.

We found that if we single out individual children and young people who already consider themselves to have poor mental health, we perpetuate the otherness of experiencing emotional difficulties. This can further exacerbate poor mental health as an isolating experience, which in turn can create a myth that other people are doing alright. This creates a binary set of ideas about mental health as being either poor or good and gives children and young people the false impression that we are either happy or sad, coping or not coping.

I believe that this attitude towards mental health is contributing to us losing sight of the emotional complexity of the human condition. In reality it is normal to feel a wide range of emotions—including feelings such as worry, sadness, contentment, anger, happiness, and relief—but we are not teaching our children and teenagers this. Instead, we pathologise and catastrophise difficult emotions when they arise, and escalate and create potential crises by speaking in limited diagnostic terms (currently our societal focus is on anxiety and trauma).

For now, I believe that children and young people’s mental health will only improve if we broaden our treatment of mental health and move away from our current deficit model which is very individualistic in focus. Instead, it would be far healthier to work with all children as part of a not for profit or school curriculum and to include the psychology of happiness, satisfaction, and what makes for a meaningful life alongside addressing challenges in our everyday treatment of mental health.

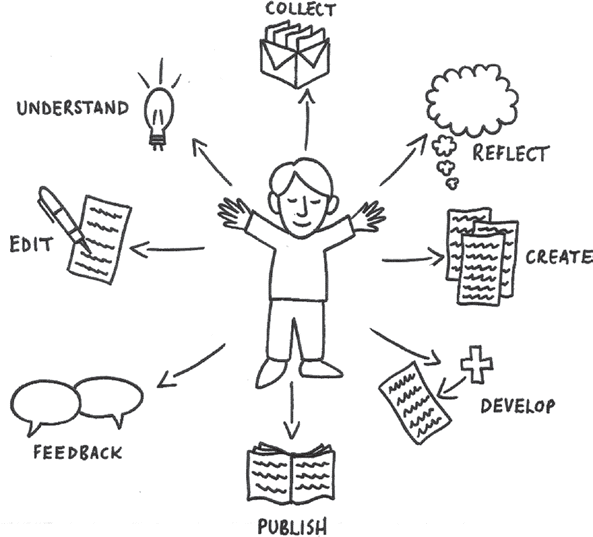

Drawing upon case study examples I show that it is possible to work creatively with children and teenagers in group settings and that given the opportunity, most young people enjoy taking part in a wide range of activities designed to create change in how they think about themselves and respond to others. I know from working in this way that the process makes a positive difference to how individuals feel and how they go on to cope with problems when they arise. The work that young people and I did together also challenges an overt societal focus on the individual with mental health issues, and shows the benefit of learning from peers, and also celebrating acts of kindness in ourselves and others.

Rather than problematise childhood surely, we would all rather children and young people foster hope about themselves and their futures? It is exactly this that my book sets out to do and show a wide range of practitioners how to replicate.

Rachel Burr, 2023

Rachel Burr is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Education and Social Work at the University of Sussex. An anthropologist and social worker with an international background in child protection, her overarching focus is on developing practitioner-orientated techniques for working with and enhancing emotional strength among children and young people who are living in challenging and difficult circumstances.

Her most recent book Self-worth in children and young people – Critical and practical considerations challenges the dominant approaches to children and young people’s mental health, and provides straightforward practical strategies that can be used to address emotional upset, loss and aid recovery.